Two Routes to the Truth

Case / External content not produced by TOW Project

This case/example originally appeared in Sky & Telescope Magazine, June 2017. In it, S&T Science Editor Camille M. Carlisle describes how her faith informs her work as a science journalist.

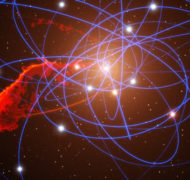

Many readers are familiar by now with my fondness for black holes. For me, black holes are the Labrador puppies of the cosmos — so cute, so delighted by existence that in their merriment they’re unintentionally destructive.

But there’s something I love more than black holes. That something is a Someone.

God.

Astronomy is, in many ways, the bone and marrow of my life. But God’s presence is the heartbeat. Like a heartbeat, He’s often almost imperceptible. But I sense Him like a pulse, just beneath the surface of reality.

It’s something too many of us forget, that reality has layers. Occasionally people ask me how I can be Catholic and a science journalist. The answer is simple: Truth does not contradict truth. Both science and religion are a pursuit of truth. They’re after different aspects of truth, different layers of reality, but they’re still both fundamentally about truth.

Science itself is based on the assumption that truth exists. Science wouldn’t work without it. We assume that there’s a right and a wrong way to describe the universe. Dark matter exists or it doesn’t. Quantum mechanics is right or it’s wrong. It isn’t right for some folks and wrong for others. Truth is truth whether we know the truth or not; Earth revolved around the Sun even when people thought it was the other way around.

Science teaches us, in other words, that absolute truth exists. It doesn’t tell us why, or Who that Truth is. Science is a marvelous tool, but in our marveling we must not forget that science is our interaction with and understanding of physical reality. It’s immensely powerful, but it’s not metaphysical; it can’t grasp God. Trying to prove or disprove God with science is like trying to screw in a flat-head nail with a screwdriver. The handyman, discovering that he can’t find grooves in the head of the “screw,” concludes that the nail doesn’t exist. But that’s ridiculous. The nail is there, he just didn’t use the right tool. And any handyman worth his toolbox doesn’t use a screwdriver on every job.

So, too, trying to “catch” God with science, or concluding that He can’t be real because His beautiful universe is too much about drama and too little about perfect engineering (“It’s not how I would design it!” we complain) is using the wrong tool for the job.

So what is the right tool? Reason is one of them. God gave us our reason, and He wants us to use it. St. Augustine of Hippo, one of the greatest minds of his time, came to know God better by asking hard questions. In my life I, too, have found that God can stand up to any question I throw at Him. It might take years to find the answer, but it exists.

Prayer is another tool. If you want to know someone, you have to spend time with that person. My faith is not merely a head faith, founded on careful research and principles. I have heard, felt, and seen God — transcendent peace while reading Scripture, a Eucharist that at one moment is just a wafer and the next is a Presence radiating love so real I can almost see it shimmer, so powerful that I cry. God is real, and He loves us tenderly and passionately. This also is truth. It’s not a truth I’ll find in my astronomy textbooks, but it’s one I know in my core.