Vocation Focus: Making Music Out of Noise

Blog / Produced by The High Calling

I’m writing from a small sound room with an eleven-year old, her violin, and her instructor—the Concertmaster for the Harrisburg Symphony Orchestra. The girl is weaving together Concerto No. 5, 1st Movement, by Friedrich Seitz straight out of the case. I wonder how I’ll concentrate; she’s pretty good.

Despite having an appreciation for composition, three grandparents with masters' degrees in music, and an involuntary tendency to cringe at mistuned strings, I watch the instructor stop her occasionally for reasons I cannot understand.

Here he taps her elbow. Again he suggests she lighten her thumb.

I don’t hear what he hears. She’s unpolished, certainly, and I generally understand his reasoning; only I can’t hear what he’s trying to correct. If asked about a particular measure, I’d have to say, “Something is off, I’m just not sure what.” He, on the other hand—an accomplished first-chair violinist—knows precisely how the concerto should sound and precisely how to get her to play it.

This much is clear: his methodology proves that good music comes from the whole person—knowledge, posture, pace, emotion. Through attentive corrections, he brings her into alignment until her pretty-good gets better.

She’s making music.

Vocational Noise

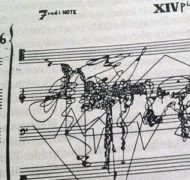

When it comes to vocational focus—an area where clarity means a great deal to me—I’m struggling. I know what my passions are. I thank God for all of them. I also want those who care to listen to hear a recognizable song in my work. Some might even find inspiration in it. But it’s unpolished. It’s cluttered with extra notes and inefficient labor, distractions and short-term vision. I’m at a point in life where my work often sounds too much like noise and not enough like music.

If my career were a symphony, then every task within it is an instrument, and I’m the undisciplined conductor admitting more musicians than I know what to do with. Alone they play beautifully, but this surplus aggregation confounds because I’ve said yes to anyone with fingers, lungs, and a half-interest in playing. Every task seems like an opportunity to expand my symphony. You can see the dilemma, can’t you? With too many parts and too little focus, I’ve become overwhelmed, unable to move the pit from tuning to performing.

Like the eleven-year old, I need help removing the noise.

Coping with HTMS

Part of the problem is this: I have a syndrome my friends call HTMS—Hate to Miss Something. It flares up when I'm invited to a movie and a hike on the same afternoon. I feel its paralysis when faced with almond-crusted tilapia and apricot chicken on the same menu. I want both. At work, it’s no different. I have numerous interests, many of which I’m capable of doing well, and because I’m also turned on by the potential bits of affirmation related to pursuing these interests, I end up committing an awful lot of yesses. In turn, I end up where I am—with an awful lot of noise.

Focus could go far in making my pretty-good into something better. Here, my father-in-law comes to mind.

For more than four decades, Dennis took the same 16-mile route to work. He wore the same clothes (fashionable ties accounted for). He served the same clients. From every Monday to every Friday, he defined a career trajectory whose simplicity appealed to me as somehow purer. I met him early enough to watch this pattern for the 15 years leading up to retirement. That’s 3,750 remarkable repetitions of focus. And he loved it.

I imagined hating it.

Too redundant, too boring. Yesses promise adventure. For as much noise as they add, I can’t imagine listening to the same single instrument every day. Does this mean that inspiration, such as Eugene Peterson’s expression, “a long obedience in the same direction,” only champions people like my father-in-law? It doesn’t exactly fit my flittering. I could aspire to “a long obedience in multiple directions,” but what motivational speaker could earn her keep with that floundering mantra?

Three Months of Harmonious Complexity

Allure of focus and poetic epitaphs aside, multiplicity may be the only viable way forward for me. Of course, fragmentation has to go. Distortion must be addressed, too. There is a great difference between symphony and cacophony, with one inviting me into a movement of “harmonious complexity” and the other into dissonance. These truths the violin instructor knows well.

To start, I’m taking a sabbatical. Three months could result in more yesses still, more causes for noise, it’s true. They could also provide just the right quiet for greater alignment. Regardless, whether I discover how to focus sharply or continue feeding my many passions, I’m ready for a change. “Seek first the Kingdom” feels like a good place to start.

I’m ready to have my vocational elbow tapped.

______________________________

Sam Van Eman is the young professionals editor at The High Calling and Staff Specialist at the CCO. His most recent project was narrating A Beautiful Trench It Was.

Vocation Focus

The constant noise of the digital age requires us to work that much harder to remain focused on our individual passions and the good work to which God has called us. God wants us to feel passionate about our work because what we do reflects the person we are called to serve—Jesus. Our series, Vocation Focus, will inspire you with stories, Bible reflections, and practical tips. Click now to read more about Vocation Focus.

Featured image by romana klee. Used with Permission. Source via Flickr.