Theology of Work Bible Commentary: Old Testament

Introduction to Genesis 1-11

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of ContentsThe book of Genesis is the foundation for the theology of work. Any discussion of work in biblical perspective eventually finds itself grounded on passages in this book. Genesis is incomparably significant for the theology of work because it tells the story of God’s work of creation, the first work of all and the prototype for all work that follows. God is not dreaming an illusion but creating a reality. The created universe that God brings into existence then provides the material of human work—space, time, matter and energy. Within the created universe, God is present in relationship with his creatures and especially with people. Laboring in God’s image, we work in creation, on creation, with creation and—if we work as God intends—for creation.

In Genesis we see God at work, and we learn how God intends us to work. We both obey and disobey God in our work, and we discover that God is at work in both our obedience and disobedience. The other sixty-five books of the Bible each have their own unique contributions to add to the theology of work. Yet they all spring from the source found here, in Genesis, the first book of the Bible.

God Creates the World (Genesis 1:1-2:3)

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of ContentsThe first thing the Bible tells us is that God is a creator. “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth” (Gen. 1:1, NRSV alternate reading). God speaks and things come into being that were not there before, beginning with the universe itself. Creation is solely an act of God. It is not an accident, a mistake, or the product of an inferior deity, but the self-expression of God.

God Brings the Material World into Being (Genesis 1:2)

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of Contents

Why Business Matters to God, Jeff Van Duzer (Click to Watch) |

Genesis continues by emphasizing the materiality of the world. “The earth was a formless void and darkness covered the face of the deep, while a wind from God swept over the face of the waters” (Gen. 1:2). The nascent creation, though still “formless,” has the material dimensions of space (“the deep”) and matter (“waters”), and God is fully engaged with this materiality (“a wind from God swept over the face of the waters”). Later, in chapter 2, we even see God working the dirt of his creation. “The Lord God formed man from the dust of the ground” (Gen. 2:7). Throughout chapters 1 and 2, we see God engrossed in the physicality of his creation.

Any theology of work must begin with a theology of creation. Do we regard the material world, the stuff we work with, as God’s first-rate stuff, imbued with lasting value? Or do we dismiss it as a temporary job site, a testing ground, a sinking ship from which we must escape to get to God’s true location in an immaterial “heaven.” Genesis argues against any notion that the material world is any less important to God than the spiritual world. Or putting it more precisely, in Genesis there is no sharp distinction between the material and the spiritual. The ruah of God in Genesis 1:2 is simultaneously “breath,” “wind,” and “spirit” (see footnote b in the NRSV or compare NRSV, NASB, NIV, and KJV). “The heavens and the earth” (Gen. 1:1; 2:1) are not two separate realms, but a Hebrew figure of speech meaning “the universe”[1] in the same way that the English phrase “kith and kin” means “relatives.”

Most significantly, the Bible ends where it begins—on earth. Humanity does not depart the earth to join God in heaven. Instead, God perfects his kingdom on earth and calls into being “the holy city, the new Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God” (Rev. 21:2). God’s dwelling with humanity is here, in the renewed creation. “See, the home of God is among mortals” (Rev. 21:3). This is why Jesus told his disciples to pray in the words, “Your kingdom come. Your will be done, on earth as it is in heaven” (Matt. 6:10). During the time between Genesis 2 and Revelation 21, the earth is corrupted, broken, out of kilter, and filled with people and forces that work against God’s purposes. (More on this in Genesis 3 and following.) Not everything in the world goes according to God’s design. But the world is still God’s creation, which he calls “good.” (For more on the new heaven and new earth, see “Revelation 17-22” in Revelation and Work.)

Many Christians, who work mostly with material objects, say it seems that their work matters less to the church—and even to God—than work centering on people, ideas, or religion. A sermon praising good work is more likely to use the example of a missionary, social worker, or teacher than a miner, auto mechanic, or chemist. Fellow Christians are more likely to recognize a call to become a minister or doctor than a call to become an inventory manager or sculptor. But does this have any biblical basis? Leaving aside the fact that working with people is working with material objects, it is wise to remember that God gave people the tasks both of working with people (Gen. 2:18) and working with things (Gen. 2:15). God seems to take the creation very seriously indeed.

God’s Creation Takes Work (Genesis 1:3-25; 2:7)

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of ContentsCreating a world is work. In Genesis 1 the power of God's work is undeniable. God speaks worlds into existence, and step by step we see the primordial example of the right use of power. Note the order of creation. The first three of God’s creative acts separate the formless chaos into realms of heavens (or sky), water, and land. On day one, God creates light and separates it from darkness, forming day and night (Gen. 1:3-5). On day two, he separates the waters and creates the sky (Gen. 1:6-8). On the first part of day three, he separates dry land from the sea (Gen. 1:9-10). All are essential to the survival of what follows. Next, God begins filling the realms he has created. On the remainder of day three, he creates plant life (Gen. 1:11-13). On day four he creates the sun, moon, and stars (Gen. 1:14-19) in the sky. The terms “greater light” and “lesser light” are used rather than the names “sun” and “moon,” thus discouraging the worship of these created objects and reminding us that we are still in danger of worshiping the creation instead of the Creator. The lights are beautiful in themselves and also essential for plant life, with its need for sunshine, nighttime, and seasons. On day five, God fills the water and sky with fish and birds that could not have survived without the plant life created earlier (Gen. 1:20-23). Finally, on day six, he creates the animals (Gen. 1:24-25) and—the apex of creation—humanity to populate the land (Gen. 1:26-31).[1]

In chapter 1, God accomplishes all his work by speaking. “God said…” and everything happened. This lets us know that God’s power is more than sufficient to create and maintain the creation. We need not worry that God is running out of gas or that the creation is in a precarious state of existence. God’s creation is robust, its existence secure. God does not need help from anyone or anything to create or maintain the world. No battle with the forces of chaos threatens to undo the creation. Later, when God chooses to share creative responsibility with human beings, we know that this is God’s choice, not a necessity. Whatever people may do to mar the creation or render the earth unfit for life’s fullness, God has infinitely greater power to redeem and restore.

The display of God’s infinite power in the text does not mean that God’s creation is not work, any more than writing a computer program or acting in a play is not work. If the transcendent majesty of God’s work in Genesis 1 nonetheless tempts us to think it is not actually work, Genesis 2 leaves us no doubt. God works immanently with his hands to sculpt human bodies (Gen. 2:7, 21), dig a garden (Gen. 2:8), plant an orchard (Gen. 2:9), and—a bit later—tailor “garments of skin” (Gen. 3:21). These are only the beginnings of God’s physical work in a Bible full of divine labor.[2]

Creation Is of God, but Is Not Identical with God (Genesis 1:11)

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of ContentsGod is the source of everything in creation. Yet creation is not identical with God. God gives his creation what Colin Gunton calls Selbständig-keit or a “proper independence.” This is not the absolute independence imagined by the atheists or Deists, but rather the meaningful existence of the creation as distinct from God himself. This is best captured in the description of God’s creation of the plants. “God said, ‘Let the earth put forth vegetation: plants yielding seed, and fruit trees of every kind on earth that bear fruit with the seed in it.’ And it was so" (Gen. 1:11). God creates everything, but he also literally sows the seed for the perpetuation of creation through the ages. The creation is forever dependent on God—“In him we live and move and have our being” (Acts 17:28)—yet it remains distinct. This gives our work a beauty and value above the value of a ticking clock or a prancing puppet. Our work has its source in God, yet it also has its own weight and dignity.

God Sees that His Work Is Good (Genesis 1:4, 10, 12, 18, 21, 25, 31)

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of ContentsAgainst any dualistic notion that heaven is good while earth is bad, Genesis declares on each day of creation that “God saw that it was good” (Gen. 1:4, 10, 12, 18, 21, 25). On the sixth day, with the creation of humanity, God saw that it was “very good” (Gen. 1:31). People—the agents through whom sin is soon to enter God’s creation—are nonetheless “very good.” There is simply no support in Genesis for the notion, which somehow entered Christian imagination, that the world is irredeemably evil and the only salvation is an escape into an immaterial spiritual world, much less for the notion that while we are on earth we should spend our time in “spiritual” tasks rather than “material” ones. There is no divorce of the spiritual from the material in God’s good world.

God Works Relationally (Genesis 1:26a)

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of ContentsEven before God creates people, he speaks in the plural, “Let us make humankind in our image” (Gen. 1:26; emphasis added). While scholars differ on whether “us” refers to a divine assembly of angelic beings or to a unique plurality-in-unity of God, either view implies that God is inherently relational.[1] It is difficult to be sure exactly what the ancient Israelites would have understood the plural to mean here. For our purposes it seems best to follow the traditional Christian interpretation that it refers to the Trinity. In any case, we know from the New Testament that God is indeed in relationship with himself—and with his creation—in a Trinity of love. In John's Gospel we learn that the Son—“the Word [who] became flesh” (John 1:14)—is present and active in creation from the beginning.

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God. All things came into being through him, and without him not one thing came into being. What has come into being in him was life, and the life was the light of all people. (John 1:1-4)

Thus Christians acknowledge our Trinitarian God, the unique Three-Persons-in-One-Being, God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Spirit, all personally active in creation.

God Limits His Work, Resting on the Seventh Day (Genesis 2:1-3)

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of ContentsAt the end of six days, God’s creation of the world is finished. This doesn’t mean that God ceases working, for as Jesus said, “My Father is still working, and I also am working” (John 5:17). Nor does it mean that the creation is complete, for, as we will see, God leaves plenty of work for people to do to bring the creation further along. But chaos had been turned into an inhabitable environment, now supporting plants, fish, birds, animals, and human beings.

God saw everything that he had made, and indeed, it was very good. And there was evening and there was morning, the sixth day. Thus the heavens and the earth were finished, and all their multitude. And on the seventh day God finished the work that he had done, and he rested on the seventh day from all the work that he had done. (Gen. 1:31-2:2; emphasis added)

God crowns his six days of work with a day of rest. While creating humanity was the climax of God's creative work, resting on the seventh day was the climax of God's creative week. Why does God rest? The majesty of God’s creation by word alone in chapter 1 makes it clear that God is not tired. He doesn’t need to rest. But he chooses to limit his creation in time as well as in space. The universe is not infinite. It has a beginning, attested by Genesis, which science has learned how to observe in light of the big bang theory. Whether it has an end in time is not unambiguously clear, in either the Bible or science, but God gives time a limit within the world as we know it. As long as time is running, God blesses six days for work and one for rest. This is a limit that God himself observes, and it later becomes his command to people, as well (Exod. 20:8-11).

God Creates and Equips People to Work (Genesis 1:26-2:25)

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of ContentsPeople Are Created in God’s Image (Genesis 1:26, 27; 5:1)

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of Contents Christopher Ziegler, "Live Out Loud: Work" |

Having told the story of God’s work of creation, Genesis moves on to tell the story of human work. Everything is grounded on God’s creation of people in his own image.

God said, “Let us make humankind in our image, according to our likeness.” (Gen. 1:26)

So God created humankind in his image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them. (Gen. 1:27)

When God created humankind, he made them in the likeness of God. (Gen. 5:1)

All creation displays God’s design, power, and goodness, but only human beings are said to be made in God’s image. A full theology of the image of God is beyond our scope here, so let us simply note that something about us is uniquely like him. It would be ridiculous to believe that we are exactly like God. We can’t create worlds out of pure chaos, and we shouldn’t try to do everything God does. "Beloved, never avenge yourselves, but leave room for the wrath of God; for it is written, ‘Vengeance is mine, I will repay, says the Lord’ " (Rom. 12:19). But the chief thing we know about God, so far in the narrative, is that God is a creator who works in the material world, who works in relationship, and whose work observes limits. We have the ability to do the same.

The rest of Genesis 1 and 2 develops human work in five specific categories: dominion, relationships, fruitfulness/growth, provision, and limits. The development occurs in two cycles, one in Genesis 1:26-2:4 and the other in Genesis 2:4-25. The order of the categories is not exactly in the same order both times, but all the categories are present in both cycles. The first cycle develops what it means to work in God’s image. The second cycle describes how God equips Adam and Eve for their work as they begin life in the Garden of Eden.

The language in the first cycle is more abstract and therefore well-suited for developing principles of human labor. The language in the second cycle is earthier, speaking of God forming things out of dirt and other elements, and is well suited for practical instruction for Adam and Eve in their particular work in the garden. This shift of language—with similar shifts throughout the first four books of the Bible—has attracted uncounted volumes of research, hypothesis, debate, and even division among scholars. Any general purpose commentary will provide a wealth of details. Most of these debates, however, have little impact on what the book of Genesis contributes to understanding work, workers, and workplaces, and we will not attempt to take a position on them here. What is relevant to our discussion is that chapter 2 repeats five themes developed earlier—in the order of dominion, provision, fruitfulness/growth, limits, and relationships—by describing how God equips people to fulfill the work we are created to do in his image. In order to make it easier to follow these themes, we will explore Genesis 1:26-2:25 category by category, rather than verse by verse. The following table gives a convenient index (with links) for those interested in exploring a particular verse immediately.

Passage (click to go to passage) |

Category (click to go to category) |

Cycle |

1 |

||

1 |

||

1 |

||

1 |

||

1 |

||

2 |

||

2 |

||

2 |

||

2 |

||

2 |

For an application of these passages, see "Help People Find their Gifts" at Country Supply Study Guide by clicking here.

Dominion (Genesis 1:26; 2:5)

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of ContentsTo work in God’s image is to exercise dominion (Genesis 1:26)

Creation and CreativityIn this article, Theology of Work Project Biblical Studies editor Sean McDonough explores what it means to exercise dominion in God's image, rather than domination. |

A consequence we see in Genesis of being created in God’s image is that we are to “have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the birds of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the wild animals of the earth, and over every creeping thing that creeps upon the earth” (Gen. 1:26). As Ian Hart puts it, "Exercising royal dominion over the earth as God's representative is the basic purpose for which God created man.... Man is appointed king over creation, responsible to God the ultimate king, and as such expected to manage and develop and care for creation, this task to include actual physical work."[1] Our work in God’s image begins with faithfully representing God.

As we exercise dominion over the created world, we do it knowing that we mirror God. We are not the originals but the images, and our duty is to use the original—God—as our pattern, not ourselves. Our work is meant to serve God’s purposes more than our own, which prevents us from domineering all that God has put under our control.

Think about the implications of this in our workplaces. How would God go about doing our job? What values would God bring to it? What products would God make? Which people would God serve? What organizations would God build? What standards would God use? In what ways, as image-bearers of God, should our work display the God we represent? When we finish a job, are the results such that we can say, “Thank you, God, for using me to accomplish this?”

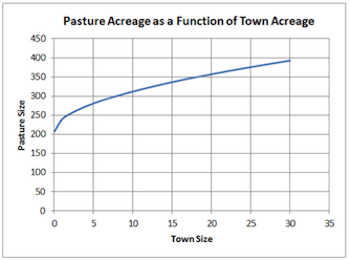

God equips people for the work of dominion (Genesis 2:5)

The cycle begins again with dominion, although it may not be immediately recognizable as such. "No plant of the field was yet in the earth and no herb of the field had yet sprung up—for the Lord God had not caused it to rain upon the earth, and there was no one to till the ground" (Gen. 2:5; emphasis added). The key phrase is “there was no one to till the ground.” God chose not to bring his creation to a close until he created people to work with (or under) him. Meredith Kline puts it this way, "God's making the world was like a king's planting a farm or park or orchard, into which God put humanity to 'serve' the ground and to 'serve' and 'look after' the estate."[2]

Thus the work of exercising dominion begins with tilling the ground. From this we see that God's use of the words subdue[3] and dominion in chapter 1 do not give us permission to run roughshod over any part of his creation. Quite the opposite. We are to act as if we ourselves had the same relationship of love with his creatures that God does. Subduing the earth includes harnessing its various resources as well as protecting them. Dominion over all living creatures is not a license to abuse them, but a contract from God to care for them. We are to serve the best interests of all whose lives touch ours; our employers, our customers, our colleagues or fellow workers, or those who work for us or who we meet even casually. That does not mean that we will allow people to run over us, but it does mean that we will not allow our self-interest, our self-esteem, or our self-aggrandizement to give us a license to run over others. The later unfolding story in Genesis focuses attention on precisely that temptation and its consequences.

Today we have become especially aware of how the pursuit of human self-interest threatens the natural environment. We were meant to tend and care for the garden (Gen. 2:15). Creation is meant for our use, but not only for our use. Remembering that the air, water, land, plants, and animals are good (Gen. 1:4-31) reminds us that we are meant to sustain and preserve the environment. Our work can either preserve or destroy the clean air, water, and land, the biodiversity, the ecosystems, and biomes, and even the climate with which God has blessed his creation. Dominion is not the authority to work against God’s creation, but the ability to work for it.

Relationships and Work (Genesis 1:27; 2:18, 21-25)

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of Contents

Engineer Turned CEO Learned to Put Relationships First in Managing People |

To Work in God’s Image Is to Work in Relationship with Others (Genesis 1:27)

A consequence we see in Genesis of being created in God’s image is that we work in relationship with God and one another. We have already seen that God is inherently relational (Gen. 1:26), so as images of a relational God, we are inherently relational. The second part of Genesis 1:27 makes the point again, for it speaks of us not individually but in twos, “Male and female he created them.” We are in relationship with our creator and with our fellow creatures. These relationships are not left as philosophical abstractions in Genesis. We see God talking and working with Adam in naming the animals (Gen. 2:19). We see God visiting Adam and Eve “in the garden at the time of the evening breeze” (Gen. 3:8).

How does this reality impact us in our places of work? Above all, we are called to love the people we work with, among, and for. The God of relationship is the God of love (1 John 4:7). One could merely say that "God loves," but Scripture goes deeper to the very core of God's being as Love, a love flowing back and forth among the Father, the Son (John 17:24), and the Holy Spirit. This love also flows out of God's being to us, doing nothing that is not in our best interest (agape love in contrast to human loves situated in our emotions).

Francis Schaeffer explores further the idea that because we are made in God's image and because God is personal, we can have a personal relationship with God. He notes that this makes genuine love possible, stating that machines can't love. As a result, we have a responsibility to care consciously for all that God has put in our care. Being a relational creature carries moral responsibility.[1]

God Equips People to Work in Relationship with Others (Genesis 2:18, 21-25)

Because we are made in the image of a relational God, we are inherently relational ourselves. We are made for relationships with God himself and also with other people. God says, “It is not good that the man should be alone; I will make him a helper as his partner” (Gen. 2:18). All of his creative acts had been called "good" or "very good," and this is the first time that God pronounces something "not good." So God makes a woman out of the flesh and bone of Adam himself. When Eve arrives, Adam is filled with joy. “This at last is bone of my bones and flesh of my flesh” (Gen. 2:23). (After this one instance, all new people will continue to come out of the flesh of other human beings, but born by women rather than men.) Adam and Eve embark on a relationship so close that “they become one flesh” (Gen. 1:24). Although this may sound like a purely erotic or family matter, it is also a working relationship. Eve is created as Adam’s “helper” and “partner” who will join him in working the Garden of Eden. The word helper indicates that, like Adam, she will be tending the garden. To be a helper means to work. Someone who is not working is not helping. To be a partner means to work with someone, in relationship.

When God calls Eve a “helper,” he is not saying she will be Adam’s inferior or that her work will be less important, less creative, less anything, than his. The word translated as “helper” here (Hebrew ezer) is a word used elsewhere in the Old Testament to refer to God himself. “God is my helper [ezer]” (Psalm 54:4). “Lord, be my helper [ezer]” (Ps. 30:10). Clearly, an ezer is not a subordinate. Moreover, Genesis 2:18 describes Eve not only as a “helper” but also as a “partner.” The English word most often used today for someone who is both a helper and a partner is “co-worker.” This is indeed the sense already given in Genesis 1:27, “male and female he created them,” which makes no distinction of priority or dominance. Domination of women by men—or vice versa—is not in accordance with God’s good creation. It is a tragic consequence of the Fall (Gen. 3:16).

Relationships are not incidental to work; they are essential. Work serves as a place of deep and meaningful relationships, under the proper conditions at least. Jesus described our relationship with himself as a kind of work, “Take my yoke upon you, and learn from me; for I am gentle and humble in heart, and you will find rest for your souls” (Matt. 11:29). A yoke is what makes it possible for two oxen to work together. In Christ, people may truly work together as God intended when he made Eve and Adam as co-workers. While our minds and bodies work in relationship with other people and God, our souls “find rest.” When we don’t work with others towards a common goal, we become spiritually restless. For more on yoking, see the section on 2 Corinthians 6:14-18 in the Theology of Work Commentary.

A crucial aspect of relationship modeled by God himself is delegation of authority. God delegated the naming of the animals to Adam, and the transfer of authority was genuine. “Whatever the man called every living creature, that was its name” (Gen. 2:19). In delegation, as in any other form of relationship, we give up some measure of our power and independence and take the risk of letting others’ work affect us. Much of the past fifty years of development in the fields of leadership and management has come in the form of delegating authority, empowering workers, and fostering teamwork. The foundation of this kind of development has been in Genesis all along, though Christians have not always noticed it.

Can You Love Your Employees? (Click Here to Read)Samantha thought the advice of her grad school professor was a little unusual—words given her as she was about to launch her career: “Don’t get too close to your co-workers,” he said. “You never know when you’re going to have to fire someone, and you don’t want to fire your close friends.” |

Many people form their closest relationships when some kind of work—whether paid or not—provides a common purpose and goal. In turn, working relationships make it possible to create the vast, complex array of goods and services beyond the capacity of any individual to produce. Without relationships at work, there are no automobiles, no computers, no postal services, no legislatures, no stores, no schools, no hunting for game larger than one person can bring down. And without the intimate relationship between a man and a woman, there are no future people to do the work God gives. Our work and our community are thoroughly intertwined gifts from God. Together they provide the means for us to be fruitful and multiply in every sense of the words.

Fruitfulness/Growth (Genesis 1:28; 2:15, 19-20)

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of ContentsTo work in God’s image is to bear fruit and multiply (Genesis 1:28)

Since we are created in God’s image, we are to be fruitful, or creative. This is often called the “creation mandate” or “cultural mandate.” God brought into being a flawless creation, an ideal platform, and then created humanity to continue the creation project. “God blessed them, and God said to them, ‘Be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth’ ” (Gen. 1:28a). God could have created everything imaginable and filled the earth himself. But he chose to create humanity to work alongside him to actualize the universe’s potential, to participate in God’s own work. It is remarkable that God trusts us to carry out this amazing task of building on the good earth he has given us. Through our work God brings forth food and drink, products and services, knowledge and beauty, organizations and communities, growth and health, and praise and glory to himself.

A word about beauty is in order. God’s work is not only productive, but it is also a “delight to the eyes” (Gen. 3:6). This is not surprising, since people, being in the image of God, are inherently beautiful. Like any other good, beauty can become an idol, but Christians have often been too worried about the dangers of beauty and too unappreciative of beauty’s value in God’s eyes. Inherently, beauty is not a waste of resources, or a distraction from more important work, or a flower doomed to fade away at the end of the age. Beauty is a work in the image of God, and the kingdom of God is filled with beauty “like a very rare jewel” (Rev. 21:11). Christian communities do well at appreciating the beauty of music with words about Jesus. Perhaps we could do better at valuing all kinds of true beauty.

A good question to ask ourselves is whether we are working more productively and beautifully. History is full of examples of people whose Christian faith resulted in amazing accomplishments. If our work feels fruitless next to theirs, the answer lies not in self-judgment, but in hope, prayer, and growth in the company of the people of God. No matter what barriers we face—from within or without—by the power of God we can do more good than we could ever imagine.

God equips people to bear fruit and multiply (Genesis 2:15, 19-20)

Official Ram Trucks Super Bowl Commercial "Farmer" |

"The Lord God took the man and put him in the Garden of Eden to till it and keep it" (Gen. 2:15). These two words in Hebrew, avad (“work” or “till”) and shamar (“keep”), are also used for the worship of God and keeping his commandments, respectively.[1] Work done according to God’s purpose has an unmistakable holiness.

Adam and Eve are given two specific kinds of work in Genesis 2:15-20, gardening (a kind of physical work) and giving names to the animals (a kind of cultural/scientific/intellectual work). Both are creative enterprises that give specific activities to people created in the image of the Creator. By growing things and developing culture, we are indeed fruitful. We bring forth the resources needed to support a growing population and to increase the productivity of creation. We develop the means to fill, yet not overfill, the earth. We need not imagine that gardening and naming animals are the only tasks suitable for human beings. Rather the human task is to extend the creative work of God in a multitude of ways limited only by God’s gifts of imagination and skill, and the limits God sets. Work is forever rooted in God's design for human life. It is an avenue to contribute to the common good and as a means of providing for ourselves, our families, and those we can bless with our generosity.

An important (though sometimes overlooked) aspect of God at work in creation is the vast imagination that could create everything from exotic sea life to elephants and rhinoceroses. While theologians have created varying lists of those characteristics of God that have been given to us that bear the divine image, imagination is surely a gift from God we see at work all around us in our workspaces as well as in our homes.

Much of the work we do uses our imagination in some way. We tighten bolts on an assembly line truck and we imagine that truck out on the open road. We open a document on our laptop and imagine the story we're about to write. Mozart imagined a sonata and Beethoven imagined a symphony. Picasso imagined Guernica before picking up his brushes to work on that painting. Tesla and Edison imagined harnessing electricity, and today we have light in the darkness and myriad appliances, electronics, and equipment. Someone somewhere imagined virtually everything surrounding us. Most of the jobs people hold exist because someone could imagine a job-creating product or process in the workplace.

Yet imagination takes work to realize, and after imagination comes the work of bringing the product into being. Actually, in practice the imagination and the realization often occur in intertwined processes. Picasso said of his Guernica, "A painting is not thought out and settled in advance. While it is being done, it changes as one's thoughts change. And when it's finished, it goes on changing, according to the state of mind of whoever is looking at it."[2] The work of bringing imagination into reality brings its own inescapable creativity.

Provision (Genesis 1:29-30; 2:8-14)

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of ContentsTo Work in God’s Image Is to Receive God’s Provision (Genesis 1:29-30)

Since we are created in God's image, God provides for our needs. This is one of the ways in which those made in God’s image are not God himself. God has no needs, or if he does he has the power to meet them all on his own. We don’t. Therefore:

God said, "See, I have given you every plant yielding seed that is upon the face of all the earth, and every tree with seed in its fruit; you shall have them for food. And to every beast of the earth, and to every bird of the air, and to everything that creeps on the earth, everything that has the breath of life, I have given every green plant for food.” And it was so. (Gen. 1:29-30)

On the one hand, acknowledging God’s provision warns us not to fall into hubris. Without him, our work is nothing. We cannot bring ourselves to life. We cannot even provide for our own maintenance. We need God’s continuing provision of air, water, earth, sunshine, and the miraculous growth of living things for food for our bodies and minds. On the other hand, acknowledging God’s provision gives us confidence in our work. We do not have to depend on our own ability or on the vagaries of circumstance to meet our need. God’s power makes our work fruitful.

God Equips People with Provision for Their Needs (Genesis 2:8-14)

The second cycle of the creation account shows us something of how God provides for our needs. He prepares the earth to be productive when we apply our work to it. “The Lord God planted a garden in Eden, in the east; and there he put the man whom he had formed" (Gen. 2:8). Though we till, God is the original planter. In addition to food, God has created the earth with resources to support everything we need to be fruitful and multiply. He gives us a multitude of rivers providing water, ores yielding stone and metal materials, and precursors to the means of economic exchange (Gen. 2:10-14). “There is gold, and the gold of that land is good” (Gen. 2:11-12). Even when we synthesize new elements and molecules or when we reshuffle DNA among organisms or create artificial cells, we are working with the matter and energy that God brought into being for us.

God Sets Limits (Genesis 2:3; 2:17)

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of ContentsTo Work in God’s Image Is to Be Blessed by the Limits God Sets (Genesis 2:3)

Making Time Off Predictable and RequiredRead more here about a new study regarding rhythms of rest and work done at the Boston Consulting Group by two professors from Harvard Business School. It showed that when the assumption that everyone needs to be always available was collectively challenged, not only could individuals take time off, but their work actually benefited. (Harvard Business Review may show an ad and require registration in order to view the article.) Mark Roberts also discusses this topic in his Life for Leaders devotional "Won't Keeping the Sabbath Make Me Less Productive?" |

Since we are created in God’s image, we are to obey limits in our work. "God blessed the seventh day and hallowed it, because on it God rested from all the work that he had done in creation" (Genesis 2:3). Did God rest because he was exhausted, or did he rest to offer us image-bearers a model cycle of work and rest? The fourth of the Ten Commandments tells us that God’s rest is meant as an example for us to follow.

Remember the sabbath day, and keep it holy. Six days you shall labor and do all your work. But the seventh day is a sabbath to the Lord your God; you shall not do any work—you, your son or your daughter, your male or female slave, your livestock, or the alien resident in your towns. For in six days the Lord made heaven and earth, the sea, and all that is in them, but rested the seventh day; therefore the Lord blessed the sabbath day and consecrated it. (Exod. 20:8-11)

While religious people over the centuries tended to pile up regulations defining what constituted keeping the Sabbath, Jesus said clearly that God made the Sabbath for us–for our benefit (Mark 2:27). What are we to learn from this?

When, like God, we stop our work on whatever is our seventh day, we acknowledge that our life is not defined only by work or productivity. Walter Brueggemann put it this way, "Sabbath provides a visible testimony that God is at the center of life—that human production and consumption take place in a world ordered, blessed, and restrained by the God of all creation."[1] In a sense, we renounce some part of our autonomy, embracing our dependence on God our Creator. Otherwise, we live with the illusion that life is completely under human control. Part of making Sabbath a regular part of our work life acknowledges that God is ultimately at the center of life. (Further discussions of Sabbath, rest, and work can be found in the sections on "Mark 1:21-45," "Mark 2:23-3:6," "Luke 6:1-11," and "Luke 13:10-17" in the Theology of Work Commentary.)

God Equips People to Work within Limits (Genesis 2:17)

Having blessed human beings by his own example of observing workdays and Sabbaths, God equips Adam and Eve with specific instructions about the limits of their work. In the midst of the Garden of Eden, God plants two trees, the tree of life and the tree of the knowledge of good and evil (Gen. 2:9). The latter tree is off limits. God tells Adam, "You may freely eat of every tree of the garden; but of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil you shall not eat, for in the day that you eat of it you shall die" (Gen. 2:16-17).

Theologians have speculated at length about why God would put a tree in the Garden of Eden that he didn’t want the inhabitants to use. Various hypotheses are found in the general commentaries, and we need not settle on an answer here. For our purposes, it is enough to observe that not everything that can be done should be done. Human imagination and skill can work with the resources of God’s creation in ways inimical to God’s intents, purposes, and commands. If we want to work with God, rather than against him, we must choose to observe the limits God sets, rather than realizing everything possible in creation.

Francis Schaeffer has pointed out that God didn't give Adam and Eve a choice between a good tree and an evil tree, but a choice whether or not to acquire the knowledge of evil. (They already knew good, of course.) In making that tree, God opened up the possibility of evil, but in doing so God validated choice. All love is bound up in choice; without choice the word love is meaningless.[2] Could Adam and Eve love and trust God sufficiently to obey his command about the tree? God expects that those in relationship with him will be capable of respecting the limits that bring about good in creation.

In today’s places of work, some limits continue to bless us when we observe them. Human creativity, for example, arises as much from limits as from opportunities. Architects find inspiration from the limits of time, money, space, materials, and purpose imposed by the client. Painters find creative expression by accepting the limits of the media with which they choose to work, beginning with the limitations of representing three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional canvas. Writers find brilliance when they face page and word limits.

The Gift of Limits (Click to Read)How do you avoid failure? A lot of people come to a crisis in their lives that forces them to recognize their shortcomings. Jim Moats claims, "I believe that failure is the least efficient method for discovering limitations." Instead, he welcomes us to embrace our limitations, thereby allowing ourselves and others around us to flourish.[3] |

All good work respects God’s limits. There are limits to the earth’s capacity for resource extraction, pollution, habitat modification, and the use of plants and animals for food, clothing, and other purposes. The human body has great yet limited strength, endurance, and capacity to work. There are limits to healthy eating and exercise. There are limits by which we distinguish beauty from vulgarity, criticism from abuse, profit from greed, friendship from exploitation, service from slavery, liberty from irresponsibility, and authority from dictatorship. In practice it may be hard to know exactly where the line is, and it must be admitted that Christians have often erred on the side of conformity, legalism, prejudice, and a stifling dreariness, especially when proclaiming what other people should or should not do. Nonetheless, the art of living as God’s image-bearers requires learning to discern where blessings are to be found in observing the limits set by God that are evident in his creation.

The Work of the “Creation Mandate” (Genesis 1:28, 2:15)

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of Contents

Grassfed Burger Franchiser Sees Work as God’s Mandate to Tend the Garden |

In describing God’s creation of humanity in his image (Gen. 1:1-2:3) and equipping of humanity to live according to that image (Gen. 2:4-25), we have explored God’s creation of people to exercise dominion, to be fruitful and multiply, to receive God’s provision, to work in relationships, and to observe the limits of creation. We noted that these have often been called the “creation mandate” or “cultural mandate,” with Genesis 1:28 and 2:15 standing out in particular:

God blessed them, and God said to them, “Be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth and subdue it; and have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the air and over every living thing that moves upon the earth.” (Gen. 1:28)

The Lord God took the man and put him in the garden of Eden to till it and keep it. (Gen. 2:15)

The use of this terminology is not essential, but the idea it stands for seems clear in Genesis 1 and 2. From the beginning God intended human beings to be his junior partners in the work of bringing his creation to fulfillment. It is not in our nature to be satisfied with things as they are, to receive provision for our needs without working, to endure idleness for long, to toil in a system of uncreative regimentation, or to work in social isolation. To recap, we are created to work as sub-creators in relationship with other people and with God, depending on God’s provision to make our work fruitful and respecting the limits given in his Word and evident in his creation.

People Fall into Sin in Work (Genesis 3:1-24)

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of Contents

Challenges We Face in Business as a Result of Sin in the World |

Until this point, we have been discussing work in its ideal form, under the perfect conditions of the Garden of Eden. But then we come to Genesis 3:1-6.

Now the serpent was more crafty than any other wild animal that the Lord God had made. He said to the woman, "Did God say, 'You shall not eat from any tree in the garden'?" The woman said to the serpent, "We may eat of the fruit of the trees in the garden; but God said, 'You shall not eat of the fruit of the tree that is in the middle of the garden, nor shall you touch it, or you shall die.' " But the serpent said to the woman, "You will not die; for God knows that when you eat of it your eyes will be opened, and you will be like God, knowing good and evil." So when the woman saw that the tree was good for food, and that it was a delight to the eyes, and that the tree was to be desired to make one wise, she took of its fruit and ate; and she also gave some to her husband, who was with her, and he ate. (emphasis added)

The serpent represents anti-god, the adversary of God. Bruce Waltke notes that God's adversary is malevolent and wiser than human beings. He's shrewd as he draws attention to Adam and Eve's vulnerability even as he distorts God's command. He maneuvers Eve into what looks like a sincere theological discussion, but distorts it by emphasizing God's prohibition instead of his provision of the rest of the fruit trees in the garden. In essence, he wants God's word to sound harsh and restrictive.

The serpent’s plan succeeds, and first Eve, then Adam, eats the fruit of the forbidden tree. They break the limits God had set for them, in a vain attempt to become “like God” in some way beyond what they already had as God’s image-bearers (Gen. 3:5). Already knowing from experience the goodness of God’s creation, they choose to become “wise” in the ways of evil (Gen. 3:4-6). Eve's and Adam's decisions to eat the fruit are choices to favor their own pragmatic, aesthetic, and sensual tastes over God's word. "Good" is no longer rooted in what God says enhances life but in what people think is desirable to elevate life. In short, they turn what is good into evil.[1]

By choosing to disobey God, they break the relationships inherent in their own being. First, their relationship together—"bone of my bones and flesh of my flesh," as it had previously been (Gen. 2:23)—is driven apart as they hide from each other under the cover of fig leaves (Gen. 3:7). Next to go is their relationship with God, as they no longer talk with him in the evening breeze, but hide themselves from his presence (Gen. 3:8). Adam further breaks the relationship between himself and Eve by blaming her for his decision to eat the fruit, and getting in a dig at God at the same time. “The woman whom you gave to be with me, she gave me fruit from the tree, and I ate” (Gen. 3:12). Eve likewise breaks humanity's relationship with the creatures of the earth by blaming the serpent for her own decision (Gen. 3:13).

Adam's and Eve’s decisions that day had disastrous results that stretch all the way to the modern workplace. God speaks judgment against their sin and declares consequences that result in difficult toil. The serpent will have to crawl on its belly all its days (Gen. 3:14). The woman will face hard labor in delivering children, and also feel conflict over her desire for the man (Gen. 3:16). The man will have to toil to wrest a living from the soil, and it will produce “thorns and thistles” at the expense of the desired grain (Gen. 3:17-18). All in all, human beings will still do the work they were created to do, and God will still provide for their needs (Gen. 3:17-19). But work will become more difficult, unpleasant, and liable to failure and unintended consequences.

It is important to note that when work became toil, it was not the beginning of work. Some people see the curse as the origin of work, but Adam and Eve had already worked the garden. Work is not inherently a curse, but the curse affects the work. In fact, work becomes more important as a result of the Fall, not less, because more work is required now to yield the necessary results. Furthermore, the source materials from which Adam and Eve sprang in God’s freedom and pleasure now become sources of subjugation. Adam, made from dirt, will now struggle to till the soil until his body returns to dirt at his death (Gen. 3:19); Eve, made from a rib in Adam’s side, will now be subject to Adam’s domination, rather than taking her place beside him (Gen. 3:16). Domination of one person over another in marriage and work was not part of God's original plan, but sinful people made it a new way of relating when they broke the relationships that God had given them (Gen. 3:12-13).

Two forms of evil confront us daily. The first is natural evil, the physical conditions on earth that are hostile to the life God intends for us. Floods and droughts, earthquakes, tsunamis, excessive heat and cold, disease, vermin, and the like cause harm that was absent from the garden. The second is moral evil, when people act with wills that are hostile to God's intentions. By acting in evil ways, we mar the creation and distance ourselves from God, and we mar the relationships we have with other people.

We live in a fallen, broken world and we cannot expect life without toil. We were made for work, but in this life that work is stained by all that was broken that day in the Garden of Eden. This too is often the result of failing to respect the limits God sets for our relationships, whether personal, corporate, or social. The Fall created alienation between people and God, among people, and between people and the earth that was to support them. Suspicion of one another replaced trust and love. In the generations that followed, alienation nourished jealousy, rage, even murder. All workplaces today reflect that alienation between workers—to greater or lesser extent—making our work even more toilsome and less productive.

People Work in a Fallen Creation (Genesis 4-8)

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of ContentsWhen God drives Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden (Gen. 3:23-24), they bring with them their fractured relationships and toilsome work, scratching out an existence in resistant soil. Nonetheless, God continues to provide for them, even to the point of sewing clothes for them when they lack the skill themselves (Gen. 3:21). The curse has not destroyed their ability to multiply (Gen. 4:1-2), or to attain a measure of prosperity (Gen. 4:3-4).

The work of Genesis 1 and 2 continues. There is still ground to be tilled and phenomena of nature to be studied, described, and named. Men and women must still be fruitful, must still multiply, must still govern. But now, a second layer of work must also be accomplished—the work of healing, repairing, and restoring the things that go wrong and the evils that are committed. To put it in a contemporary context, the work of farmers, scientists, midwives, parents, leaders, and everyone in creative enterprises is still needed. But so is the work of exterminators, doctors, funeral directors, corrections officers, forensic auditors, and everyone in professions that restrain evil, forestall disaster, repair damage, and restore health. In truth, everyone’s work is a mixture of creation and repair, encouragement and frustration, success and failure, joy and sorrow. Roughly speaking, there is twice as much work to do now than there was in the garden. Work is not less important to God’s plan, but more.

The First Murder (Genesis 4:1-25)

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of ContentsGenesis 4 details the first murder when Cain kills his brother Abel in a fit of angry jealousy. Both brothers bring the fruit of their work as offerings to God. Cain is a farmer, and he brings some of the fruit of the ground, with no indication in the biblical text that this is the first or the best of his produce (Gen. 4:3). Abel is a shepherd and brings the "firstlings," the best, the “fat portions” of his flock (Gen. 4:4). Although both are producing food, they are neither working nor worshiping together. Work is no longer a place of good relationships.

God looks with favor on the offering of Abel but not on that of Cain. In this first mention of anger in the Bible, God warns Cain not to give into despair, but to master his resentment and work for a better result in the future. “If you do well, will you not be accepted?” the Lord asks him (Gen. 4:7). But Cain gives way to his anger instead and kills his brother (Gen. 4:8; cf. 1 John 3:12; Jude 11). God responds to the deed in these words:

"Listen; your brother's blood is crying out to me from the ground! And now you are cursed from the ground, which has opened its mouth to receive your brother's blood from your hand. When you till the ground, it will no longer yield to you its strength; you will be a fugitive and a wanderer on the earth." (Gen. 4:10-12)

Adam’s sin did not bring God’s curse upon people, but only upon the ground (Gen. 3:17). Cain’s sin brings the ground’s curse on Cain himself (Gen. 4:11). He can no longer till the ground, and Cain the farmer becomes a wanderer, finally settling in the land of Nod, east of Eden, where he builds the first city mentioned in the Bible (Gen. 4:16-17). (See Gen. 10-11 for more on the topic of cities.)

The remainder of chapter 4 follows Cain's descendants for seven generations to Lamech, whose tyrannical deeds make his ancestor Cain seem tame. Lamech shows us a progressive hardening in sin. First comes polygamy (Gen. 4:19), violating God's purpose in marriage in Genesis 2:24 (cf. Matt. 19:5-6). Then, a vendetta that leads him to kill someone who had merely struck him (Gen. 4:23-24). Yet in Lamech we also see the beginnings of civilization. Division of labor —which spelled trouble between Cain and Abel—brings a specialization here that makes certain advances possible. Some of Lamech’s sons create musical instruments and ply crafts using bronze and iron tools (Gen. 4:21-22). The ability to create music, to craft the instruments for playing it, and to develop technological advances in metallurgy are all within the scope of the creators we are created to be in God's image. The arts and sciences are a worthy outworking of the creation mandate, but Lamech's crowing about his vicious deeds points to the dangers that accompany technology in a depraved culture bent on violence. The first human poet after the Fall celebrates human pride and abuse of power. Yet the harp and the flute can be redeemed and used in the praise of God (1 Sam. 16:23), as can the metallurgy that went into the construction of the Hebrew tabernacle (Exod. 35:4-19, 30-35).

As people multiply, they diverge. Through Seth, Adam had hope of a godly seed, which includes Enoch and Noah. But in time there arises a group of people who stray far from God’s ways.

When people began to multiply on the face of the ground, and daughters were born to them, the sons of God saw that they were fair, and they took wives for themselves of all that they chose.... The Nephilim [giants, heroes, fierce warriors—the meaning is unclear] were on the earth in those days—and also afterward—when the sons of God went in to the daughters of humans, who bore children to them. These were the heroes that were of old, warriors of renown. The Lord saw that the wickedness of humankind was great in the earth, and that every inclination of the thoughts of their hearts was only evil continually. (Gen. 6:1-5)

What could the godly line of Seth—narrowed eventually to only Noah and his family—do against a culture so depraved that God would eventually decide to destroy it utterly?

A major workplace issue for many Christians today is how to observe the principles that we believe reflect God's will and purposes for us as his image-bearers or representatives. How can we do this in cases where our work puts us under pressure toward dishonesty, disloyalty, low-quality workmanship, unlivable wages and working conditions, exploitation of vulnerable co-workers, customers, suppliers, or the community at large? We know from Seth’s example—and many others in Scripture—that there is room in the world for people to work according to God’s design and mandate.

When others may fall into fear, uncertainty, and doubt, or succumb to unbounded desire for power, wealth, or human recognition, God’s people can remain steadfast in ethical, purposeful, compassionate work because we trust God to bring us through the hardships that may prove too much to master without God’s grace. When people are abused or harmed by greed, injustice, hatred, or neglect, we can stand up for them, work justice, and heal hurts and divisions because we have access to Christ’s redeeming power. Christians, of all people, can afford to push back against the sin we meet at our places of work, whether it arises from others’ actions or within our own hearts. God quashed the project at Babel because “nothing that they propose to do will now be impossible for them” (Gen. 11:6), for people did not refer to our actual abilities but to our hubris. Yet by God’s grace we actually do have the power to accomplish all God has in store for us in Christ, who declares that “nothing will be impossible for you” (Matt. 17:20) and “nothing will be impossible with God” (Luke 1:37).

Do we actually work as if we believe in God’s power? Or do we fritter away God’s promises by simply trying to get by without causing any fuss?

God Calls Noah and Creates a New World (Genesis 6:9-8:19)

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of ContentsSome situations may be redeemable. Others may be beyond redemption. In Genesis 6:6-8 , we hear God's lament about the state of the pre-flood world and culture, and his decision to start over:

The Lord was sorry that he had made humankind on the earth, and it grieved him to his heart. So the Lord said, "I will blot out from the earth the human beings I have created—people together with animals and creeping things and birds of the air, for I am sorry that I have made them." But Noah found favor in the sight of the Lord.

From Adam to us, God looks for persons who can stand against the culture of sin when needed. Adam failed the test but sired the line of Noah, "a righteous man, blameless in his generation; Noah walked with God" (Gen. 6:9). Noah is the first person whose work is primarily redemptive. Unlike others, who are busy wringing a living from the ground, Noah is called to save humanity and nature from destruction. In him we see the progenitor of priests, prophets, and apostles, who are called to the work of reconciliation with God, and those who care for the environment, who are called to the work of redeeming nature. To greater or lesser degrees, all workers since Noah are called to the work of redemption and reconciliation.

But what a building project the ark is! Against the jeers of neighbors, Noah and his sons must fell thousands of cypress trees, then hand plane them into planks enough to build a floating zoo. This three-deck vessel needs the capacity to carry the various species of animals and to store the food and water required for an indefinite period. Despite the hardship, the text assures us that "Noah did this; he did all that God commanded him" (Gen. 6:13-22).

In the business world, entrepreneurs are used to taking risks, working against conventional wisdom in order to come up with new products or processes. A long-term view is required, rather than attention to short-term results. Noah faces what must at times have seemed to be an impossible task, and some biblical scholars suggest that the actual building of the ark took a hundred years. It also takes faith, tenacity, and careful planning in the face of skeptics and critics. Perhaps we should add project management to the list of Noah’s pioneering developments. Today innovators, entrepreneurs, and those who challenge the prevailing opinions and systems in our places of work still need a source of inner strength and conviction. The answer is not to talk ourselves into taking foolish risks, of course, but to turn to prayer and the counsel of those wise in God when we are confronted with opposition and discouragement. Perhaps we need a flowering of Christians gifted and trained for the work of encouraging and helping refine the creativity of innovators in business, science, academia, arts, government, and the other spheres of work.

The story of the flood, found in Genesis 7:1-8:19, is well known. For more than half a year Noah, his family, and all of the animals bounce around inside the ark as the floods rage, swirling the ark in water covering the mountaintops. When at last the flood subsides, the ground is dry and new vegetation is springing up. The occupants of the ark once again step on dry land. The text echoes Genesis 1, emphasizing the continuity of creation. God blows a “wind” over “the deep” and “the waters” recede (Gen. 8:1-3). Yet it is, in a sense, a new world, reshaped by the force of the flood. God was giving human culture a new opportunity to start from scratch and get it right. For Christians, this foreshadows the new heaven and new earth in Revelation 21-22, when human life and work are brought to perfection within the cosmos healed from the effects of the Fall, as we discussed in "God brings the material world into being" (Gen. 1:1-2).

What may be less apparent is that this, humanity’s first large-scale engineering work, is an environmental project. Despite—or perhaps as a result of—humanity’s broken relationship with the serpent and all creatures (Gen. 3:15), God assigns a human being the task of saving the animals and trusts him to do it faithfully. People have not been released from God’s call to "have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the air and over every living thing that moves upon the earth" (Gen. 1:28). God is always at work to restore what was lost in the Fall, and he uses fallen-but-being-restored humanity as his chief instrument.

God’s Covenant with Noah (Genesis 9:1-19)

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of ContentsOnce again on dry land with this new beginning, Noah's first act is to build an altar to the Lord (Gen. 8:20). Here he offers sacrifices that please God, who resolves never again to destroy humanity "as long as the earth endures, seedtime and harvest, cold and heat, summer and winter, day and night, shall not cease" (Gen. 8:22). God binds himself to a covenant with Noah and his descendants, promising never to destroy the earth by flood (Gen. 9:8-17). God gives the rainbow as a sign of his promise. Although the earth has radically changed again, God’s purposes for work remain the same. He repeats his blessing and promises that Noah and his sons will “be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth” (Gen. 9:1). He affirms his promise of provision of food through their work (Gen. 9:3). In return he sets requirements for justice among humans and for the protection of all creatures (Gen. 9:4-6).

The Hebrew word translated "rainbow" actually omits the sense of “rain.” It refers simply to a bow—a battle and hunting tool. Waltke notes that in ancient Near East mythologies, stars in the shape of a bow were associated with the anger or hostility of the god, but that “here the warrior’s bow is hung up, pointed away from the earth.”[1] Meredith Kline observes that "the symbol of divine bellicosity and hostility has been transformed into a token of reconciliation between God and man."[2] The relaxed bow stretches from earth to heaven, from horizon to horizon. An instrument of war has become a symbol of peace through God's covenant with Noah.

Noah’s Fall (Genesis 9:20-29)

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of ContentsAfter his heroic work on behalf of humanity, Noah falls into a troubling domestic incident. It begins—as so many domestic and workplace tragedies do—with substance abuse, in this case alcohol. (Add alcoholic beverage production to the list of Noah’s innovations; Gen. 9:20.) After becoming drunk, Noah passes out naked in his tent. His son Ham bursts in and sees him in this state, but his other sons—alerted by Ham—circumspectly enter the tent backwards and cover up their father without looking upon him in the raw. Exactly what is so shameful or immoral about this situation is hard for most modern readers to understand, but he and his sons clearly understand it to be a family disaster. When Noah regains consciousness and finds out, his response permanently destroys the family’s tranquility. Noah curses Ham’s descendants via Canaan and makes them slaves to the other two sons’ branches. This sets the stage for thousands of years of enmity, war, and atrocity among Noah’s family.

Noah may be the first person of great stature to come crashing down into disgrace, but he was not the last. Something about greatness seems to make people vulnerable to moral failure—especially, it seems, in our personal and family lives. In an instant, all of us could name a dozen examples on the world stage. The phenomenon is common enough to spawn proverbs, whether biblical—“Pride goes before destruction, and a haughty spirit before a fall” (Prov. 16:18)—or colloquial—“The bigger they come, the harder they fall.”

Noah is undoubtedly one of the great figures of the Bible (Heb. 11:7), so our best response is not to judge Noah but to ask God’s grace for ourselves. If we find ourselves seeking greatness, it's better to seek humility first. If we have become great, it's best to beg God for the grace to escape Noah’s fate. If we have fallen, similarly to Noah, let us confess swiftly and ask those around us to prevent us from turning a fall into a disaster through our self-justifying responses.

Noah’s Descendants and the Tower of Babel (Genesis 10:1-11:32)

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of ContentsIn what is called the Table of Nations, Genesis 10 traces first the descendants of Japheth (Gen. 10:2-5), then the descendants of Ham (Gen. 10:6-20), and finally the descendants of Shem (Gen. 10:21-31). Among them, Ham’s grandson Nimrod stands out for his significance to the theology of work. Nimrod founds an empire of naked aggression based in Babylon. He is a tyrant, a mighty hunter to be feared, and most significantly a builder of cities (Gen. 10:8-12).

With Nimrod, the tyrannical city-builder, fresh in our memory, we come to the building of the tower of Babel (Gen. 11:1-9). Babel, like many cities in the ancient Near East is designed as a walled enclosure of a great temple or ziggurat, a mud-brick stair tower designed to reach to the realm of the gods. With such a tower, people could ascend to the gods, and the gods could descend to earth. Although God does not condemn this drive to reach the heavens, we see in it the self-aggrandizing ambition and escalating sin of pride that drives these people to begin building such a mighty tower. "Let us build ourselves a city, and a tower with its top in the heavens, and let us make a name for ourselves; otherwise we shall be scattered abroad upon the face of the whole earth" (Gen. 11:4). What did they want? Fame. What did they fear? Being scattered without the security of numbers. The tower they envisioned building seemed huge to them, but the Genesis narrator smiles while telling us that it was so puny that God "came down to see the city and the tower" (Gen. 11:5). How different from the city of peace, order, and virtue that are God’s purposes for the world.[1]

God’s objection to the tower is that it will give people the expectation that “nothing that they propose to do will now be impossible for them" (Gen. 11:6). Like Adam and Eve before them, they intend to use the creative power they possess as image-bearers of God to act against God’s purposes. In this case, they plan to do the opposite of what God commanded in the cultural mandate. Instead of filling the earth, they intend to concentrate themselves here in one location. Instead of exploring the fullness of the name God gave them—adam, “humankind” (Gen. 5:2)—they decide to make a name for themselves. God sees that their arrogance and ambition are out of bounds and says, "Let us go down and confuse their language there, so that they will not understand one another's speech” (Gen. 11:7). Then “the Lord scattered them abroad from there over the face of all the earth, and they left off building the city. Therefore it was called Babel, because there the Lord confused the language of all the earth; and from there the Lord scattered them abroad over the face of all the earth” (Gen. 11:8-9).

We might be tempted to conclude from this study that cities are inherently bad, but this is not so. God gave Israel their capital city of Jerusalem, and the ultimate abode of God’s people is God's holy city coming down from heaven (Rev. 21:2). The concept of "city" is not evil, but the pride that we may come to attach to cities is what displeases God (Gen. 19:12-14). We sin when we look to civic triumph and culture, in place of God, as our source of meaning and direction. Bruce Waltke concludes his analysis of Genesis 11 in these words:

Society apart from God is totally unstable. On the one hand, people earnestly seek existential meaning and security in their collective unity. On the other hand, they have an insatiable appetite to consume what others possess....At the heart of the city of man is love for self and hatred for God. The city reveals that the human spirit will not stop at anything short of usurping God's throne in heaven.[2]

While it might appear that God’s scattering of the peoples is a punishment, in fact it is also a means of redemption. From the beginning, God intended people to disperse across the world. “Be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth” (Gen. 1:28). By scattering people after the fall of the tower, God put people back on the path of filling the earth, ultimately resulting in the beautiful array of peoples and cultures that populate it today. If people had completed the tower under a singularity of malicious intent and social tyranny, with the result that “nothing that they propose to do will now be impossible for them" (Gen. 11:6), we can only imagine the horrors they would have worked in their pride and strength of sin. The scale of evil worked by humanity in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries gives a mere glimpse of what people might do if all things were possible without dependence on God. As Dostoevsky put it, “Without God and the future life, it means everything is permitted.”[3] Sometimes God will not give us our way because his mercy toward us is too great.

What can we learn from the incident of the Tower of Babel for our work today? The specific offense the builders committed was disobeying God’s command to spread out and fill the earth. They centralized not only their geographical dwellings, but also their culture, language, and institutions. In their ambition to do one great thing ("make a name for ourselves" [Gen. 11:4]), they stifled the breadth of endeavor that ought to come with the varieties of gifts, services, activities, and functions with which God endows people (1 Cor. 12:4-11). Although God wants people to work together for the common good (Gen. 2:18; 1 Cor. 12:7), he has not created us to accomplish it through centralization and accumulation of power. He warned the people of Israel against the dangers of concentrating power in a king (1 Sam. 8:10-18). God has prepared for us a divine king, Christ our Lord, and under him there is no place for great concentration of power in human individuals, institutions, or governments.

So, then, we could expect Christian leaders and institutions to be careful to disperse authority and to favor coordination, common goals and values, and democratic decision-making instead of concentration of power. But in many cases Christians have sought something different, the same kind of concentration of power that tyrants and authoritarians seek, though with more benevolent goals. In this mode, Christian legislators seek just as much control over the populace, though with the object of enforcing piety or morality. In this mode, Christian business people seek as much oligopoly as others, though for the purpose of enhancing quality, customer service, or ethical behavior. In this mode, Christian educators seek as little freedom of thought as authoritarian educators do, though with the intent of enforcing moral expression, kindness, and sound doctrine.

As laudable as all these goals are, the events of the Tower of Babel suggest they are often dangerously misguided (God’s later warning to Israel about the dangers of having a king echo this suggestion; see 1 Sam. 8:10-18). In a world where even those in Christ still struggle with sin, God’s idea of good dominion (by humans), seems to be to disperse people, power, authority, and capabilities, rather than concentrating it in one person, institution, party, or movement. Of course, some situations demand decisive exercise of power by one person or a small group. A pilot would be foolish to take a passenger vote about which runway to land on. But could it be that more often than we realize, when we are in positions of power, God is calling us to disperse, delegate, authorize, and train others, rather than exercising it all ourselves? Doing so is messy, inefficient, hard to measure, risky, and anxiety-inducing. But it may be exactly what God calls Christian leaders to do in many situations.

Conclusions from Genesis 1-11

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of ContentsIn the opening chapters of the Bible, God creates the world and brings us forth to join him in further creativity. He creates us in his image to exercise dominion, to be fruitful and multiply, to receive his provision, to work in relationship with him and with other people, and to observe the limits of his creation. He equips us with resources, abilities, and communities to fulfill these tasks, and gives us the pattern of working toward them six days out of seven. He gives us the freedom to do these things out of love for him and his creation, which also gives us the freedom to not do the things for which he created us. To our lasting injury, the first human beings chose to violate God’s mandate, and people have continued to choose disobedience—to a greater or lesser degree—to the present day. As a result, our work has become less productive, more toilsome, and less satisfying, and our relationships and work are diminished and at times even destructive.

Nonetheless, God continues to call us to work, equipping us and providing for our needs. And many people have the opportunity to do good, creative, fulfilling work that provides for their needs and contributes to a thriving community. The Fall has made the work that began in the Garden of Eden more necessary, not less. Although Christians have sometimes misunderstood this, God did not respond to the Fall by withdrawing from the material world and confining his interests to the spiritual, nor is it possible to divorce the material and the spiritual anyway. Work, including the relationships that pervade it and the limits that bless it, remains God’s gift to us, even if it is severely marred by the conditions of existence after the Fall.

At the same time, God is always at work to redeem his creation from the effects of the Fall. Genesis 4-11 begins the story of how God's power is working to order and reorder the world and its inhabitants. God is sovereign over the created world and over every living creature, human and otherwise. He continues to tend to his own image in humanity. But he does not tolerate human efforts to "be like God" (Gen. 3:5) in order either to acquire excessive power or to substitute self-sufficiency for relationship with God. Those, like Noah, who receive work as a gift from God and do their best to work according to his direction, find blessing and fruitfulness in their work. Those, like the builders of the tower of Babel, who try to grasp power and success on their own terms, find violence and frustration, especially when their work turns toward harming others. Like all the characters in these chapters of Genesis, we face the choice of whether to work with God or in opposition to him. How the story of God’s work to redeem his creation will turn out is not told in the book of Genesis, but we know that it ultimately leads to the restoration of creation—including the work of God’s creatures—as God has intended from the beginning.

For Further Reading

Mark Biddle, Missing the Mark: Sin and Its Consequences in Biblical Theology (Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press, 2005).

Walter Brueggemann, Genesis (Atlanta: John Knox, 1982).

Victor Hamilton, The Book of Genesis: Chapters 1-17 (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1990).

Walter Kaiser Jr., Toward Old Testament Ethics (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1983).

Thomas Keiser, Genesis 1-11: Its Literary Coherence and Theological Message (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2013).

John Mason, “Biblical Teaching and Assisting the Poor,” Interpretation 4, no.2 (1987).

John Mason and Kurt Schaefer, “The Bible, the State, and the Economy: A Framework for Analysis,” Christian Scholar’s Review 20, no. 1 (1990).

Kenneth Mathews, The New American Commentary: Vol. 1A Genesis 1-11.26 (Nashville: Broadman and Holman, 1996).

Gerhard von Rad, Genesis rev. edn. (London: SCM, 1972).

Bruce Vawter, On Genesis: A New Reading (New York: Doubleday, 1977).

John Walton, The NIV Application Commentary: Genesis (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2001).

Claus Westermann, Genesis 1-11 (Minneapolis: Augsburg, 1984).

Albert Wolters, Creation Regained (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2005).

Christopher Wright, Old Testament Ethics for the People of God (Leicester: Inter-Varsity Press, 2004).

Continue to Genesis 12-50

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of ContentsPlease click here to read our commentary on Genesis 12-50: Genesis 12-50 and Work

Go to Genesis 1-11

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of ContentsClick here to read our commentary on Genesis 1-11: Genesis 1-11 and Work

Introduction to Genesis 12-50 and Work

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of ContentsGenesis chapters 12 through 50 tell about the life and work of Abraham, Sarah, and their descendants. God called Abraham, Sarah, and their family to leave their homeland for the new country that God would show them. Along the way, God promised to make them into a great nation: “In you all the families of the earth shall be blessed” (Gen. 12:3). As Abraham’s spiritual descendants, blessed by this great family and brought to faith through their descendant Jesus Christ, we are called to follow in the footsteps of the faith of the father and mother of all who truly believe (Rom. 4:11; Gal. 3:7, 29).